This article was originally published in 1965 in Life Magazine and the photographs are by Allan Grant. This has been published here without permission for historical, educational, and awareness purposes only. The layout has been modified to make reading easier on mobile devices.

This article describes the birth of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and its founder, Ole Ivar Løvaas when he was 38 years old and first started his projects at UCLA. To learn more about Lovaas himself, you can check out his interview that took place about a decade later in 1974.

I am autistic and as the author of this website, I feel the need to point out that I do not agree with or condone the use of corporal or physical punishment or the abusive techniques that this article discusses. In my personal opinion, the practices that Ole Ivar Løvaas developed were highly unethical and focused more on forcing autistic children to pass as not autistic rather than the wellbeing of the autistic children themselves. There is no doubt in my mind that the victims of Løvaas experienced both physical and emotional abuse.

Click here to view a PDF version of the article as it was scanned from the printed version. Archived source.

Trigger Warning: outdated and offensive language, dehumanization of disabled people, electric shock, and child abuse.

Screams, Slaps, and Love

A surprising, shocking treatment helps far-gone mental cripples

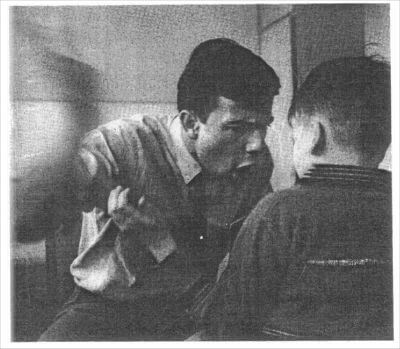

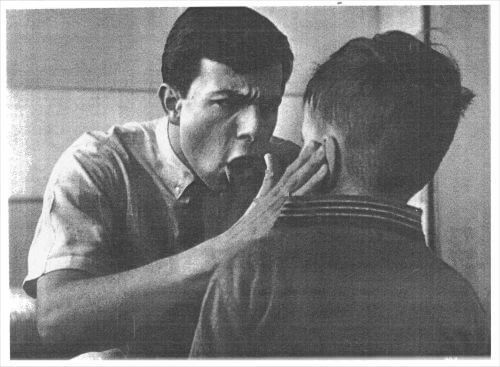

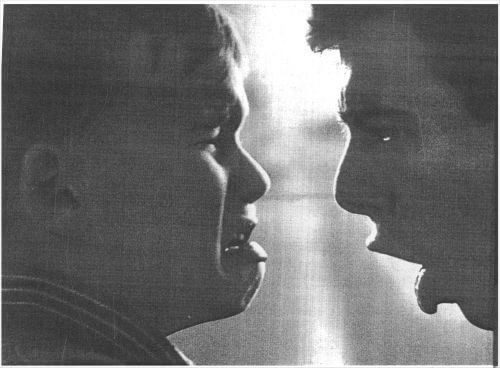

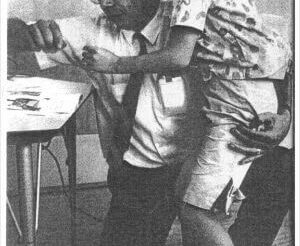

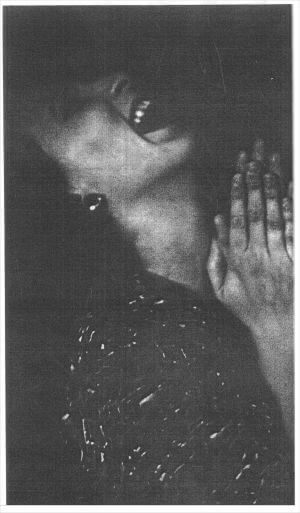

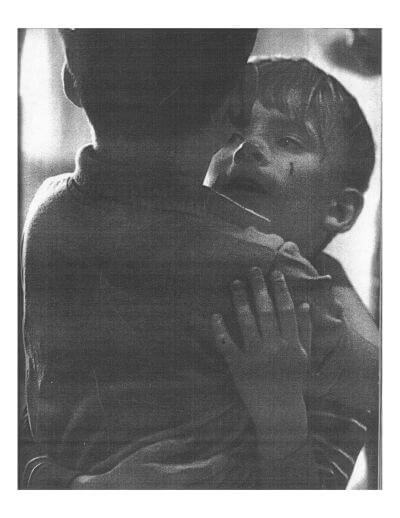

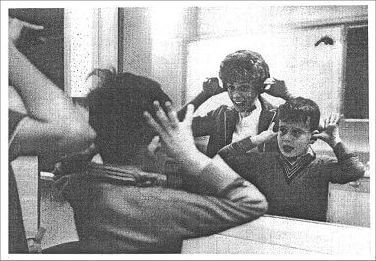

Enraged bellows at the boy, then a sharp slap in the face. This deliberate, calculated harshness is part of an extraordinary new treatment for mentally crippled children. It is based on the old-fashioned idea that the way to bring up children is to reward them when they’re good, punish them when they’re bad. At the University of California in Los Angeles, a team of researchers is applying this precept to extreme cases. They have taken on three boys and a girl with a special form of schizophrenia called autism — utterly withdrawn children whose minds are sealed against all human contact and whose uncontrolled madness had turned their homes into hells (p. 96). And, by alternating methods of shocking roughness with persistent and loving attention, the researchers have broken through the first barriers.

The set-to between the two shown on the preceding page — Researcher Bernard Perloff and a patient named Billy — began when Billy did not pay attention during his speech lesson. It ends with Billy in tears.

At the start, appalling gallery of madness

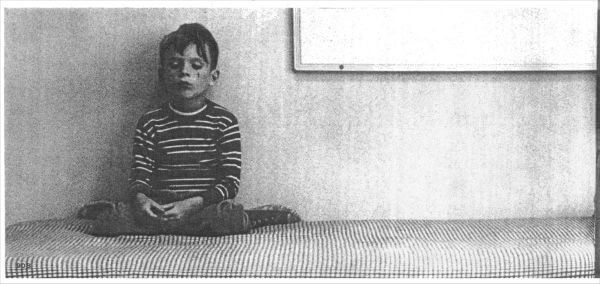

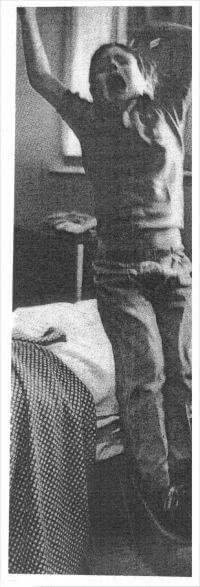

At the beginning of the UCLA tests last June, the four autistic children were assembled in a small room bare of playthings — such children do not play. Closeted in their private bedlams, they went through their endless, senseless activities. Pamela, 9, performed her macabre pantomime. and Ricky, 8, loved to flop his arms, waggle his fingers, cover his head with a blanket. Chuck, 7, would alternate his rocking with spells of sucking his thumb and whimpering. Billy. 7, like so many of the thousands of autistic children in the U.S.. would go into gigantic tantrums and fits of self-destruction, beating his head black and blue against walls.

Billy and Chuck could not talk at all. Pamela would infuriatingly parrot back everything said to her. Ricky had a photographic memory for jingles and ads which he chanted hour after hour.

The causes of their strange affliction are uncertain. Like most other autistic children, these four are healthy and coordinated, neither brain-damaged nor retarded. But the team conducting the experiment at UCLA is not interested in causes. In this, their approach goes against the grain of almost all other modern psychiatric treatment, which tries first to find the child’s “core neurosis” and then treats that.

Dr. Ivar Lovaas, the 38-year-old creator of the UCLA project, argues that “you have to put out the fire first before you worry how it started.” An assistant professor of psychology at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, Lovaas believes the whole present concept of “mental illness” is flawed because it relieves the patient of responsibility for his actions. Lovaas is convinced, on the basis of his experience and that of other researchers, that by forcing a change in a child’s outward behavior he can effect an inward psychological change. For example: if he could make Pamela go through the motions of paying attention, she would begin eventually to pay genuine attention (next page). Lovaas feels that by I) holding any mentally crippled child accountable for his behavior and 2) forcing him to act normal, he can push the child toward normality.

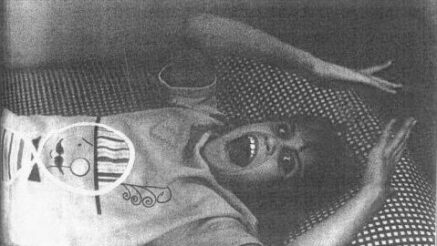

Punishment for Pamela: an electric jolt

The most drastic innovation in Lovaas’ technique is punishment — instantly, immutably dished out to break down the habits of madness. His rarely used last resort is the shock room. At one point Pamela had been making progress, learning to read a little, speak a few words sensibly. But then she came to a blank wall, drifting off during lessons into her wild expressions and gesticulations. Scoldings and stern shakings did nothing. Like many autistic children, Pamela simply did not have enough anxiety to be frightened.

To give her something to be anxious about, she was taken to the shock room, where the floor is laced with metallic strips. Two electrodes were put on her bare back, and her shoes removed.

When she resumed her habit of staring at her hand, Lovaas sent a mild jolt of current through the floor into her bare feet. It was harmless but uncomfortable. With instinctive cunning, Pamela sought to mollify Lovaas with hugs. But he insisted she go on with her reading lesson. She read for a while, then lapsed into a screaming fit. Lovaas; yelling “No!”, turned on the current. Pamela jumped — learned a new respect for “No.”

[If you think using electric shock in behavior modification is abusive and dehumanizing, you should know that this method is still in use today by The Judge Rotenberg Educational Center in Canton, Massachusets, USA.]

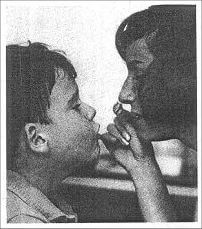

The rewards: food and affection

Even more than punishment, patience and tenderness are lavished on the children by the staff. Every hour of lesson time has a 10-minute break for affectionate play. The key to the program is a painstaking system of rewarding the children —first with food and later with approval — whenever they do something correctly. These four were picked because they are avid eaters to whom food is very important. In the first months they got no regular meals. Spoonfuls of food were doled out only for right answers.

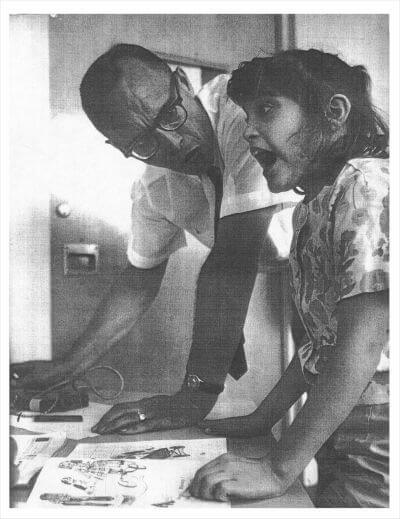

Physically demonstrating affection is one way to instill it in the children.

A case in point was teaching Billy to talk. First he had to learn how to mimic the sounds of speech. He started by learning to blow out a match with a sound like who. Every who was rewarded with food. Next he was encouraged to babble these sounds aimlessly. From time to time he would accidentally form a word. Each word got its reward. So he would repeat the accident .and after weeks had a vocabulary of words like ball, milk, mania, me.

Then they tried to teach meaning. When a ball was held up, Billy would just as likely say milk. This went on for frustrating weeks. In the sixth week the staff realized Billy was smarter than they had thought. When he gave the wrong word, the researcher would prompt him with the right word. When he echoed it, he was fed. Changing the method, the researcher held up a ball. Billy said, “Me” and got nothing. He fidgeted. Desperately he began going through his whole vocabulary. When he hit ball he was fed. In an hour Billy had caught on and could find the right word immediately. Today he can ask for any food by name, ask to go out, to go to the bathroom. In short, Billy can talk. All it took was ingenuity — and some 90,000 trials.

Chuck’s big breakthrough: a simple friendly hug

Chuck’s mother watched her son and her excitement grew. After six weeks. Chuck was beginning to behave like a normal 7-year-old. He had learned to show affection and for the first time talked in simple phrases. The two other boys had also progressed remarkably. Ricky appeared before a UCLA seminar and told them, “I am 4 feet 3 inches tall. I’m wearing black and white tennis shoes!” Billy may go to a special school next year. Pamela. the oldest, can read now but left alone still reverts to her bizarre autistic ways.

One of the leading authorities on autism has called the UCLA project “a tremendous accomplishment.” There are not yet plans for a clinic to offer general treatment, but Lovaas hopes he has found a way to help any child with a broken mind more quickly and simply than with methods now used.

On first visiting day for parents, Chuck’s mother sees his behavior through a one-way mirror and is overjoyed at what she sees.

The Nightmare of Life with Billy

By Don Moser

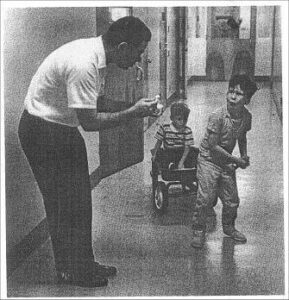

The taming and teaching of Billy takes place in the corridors and rooms of the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute where the children live during the experiment.

“When his father’s car pulled out of the driveway, I’d bolt the doors, lock the windows and the nightmare would begin.” Thus Billy’s mother, Pat, describes a terrifying existence in which she was at the mercy of a small boy so cunning and so violent that he almost propelled her into a nervous breakdown.

Pat’s story is significant in two respects. First, it indicates that it is virtually impossible for an intelligent, well-intentioned parent to cope with an autistic youngster. Second, it shows why Pat and her husband, along with the parents of the other children, so eagerly; embraced Lovaas’ program even though it involved shock and other forms of punishment.

The causes of autism are no clearer with Billy than with the other children. He had suffered a traumatic birth, one that places great strain on the infant. Pat was 17 hours in labor, and when doctors had finally delivered him by Caesarean section, it was 90 seconds before he breathed, another 90 before he cried. Nor was his early environment always pleasant. His parents’ marriage was going through a difficult period. His father, a doctor, was serving his internship; every other night he was at the hospital, and when he came home he had no energy left to do anything but fall into bed. Later, called into the Navy, he was separated from Billy and Pat for long periods.

Whatever the causes — organic, environmental or both — it was clear by the time Billy was 2 years old that something was very wrong with him. He had not started to speak. He threw uncontrollable tantrums. He never seemed to sleep. Pat and her husband took the child from one psychiatrist or neurologist to another. All gave the same analysis: Billy was retarded.

Before long, however, Pat realized that Billy was diabolically clever and hell-bent on destroying her. Whenever her husband was home, Billy was a model youngster. He knew that his father would punish him quickly and dispassionately for misbehaving. But when his father left the house, Billy would go to the window and watch until the car pulled out. As soon as it did, he was suddenly transformed. “It was like living with the devil,” Pat remembers. “He’d go into my closet and tear up my evening dresses and urinate on my clothes. He’d smash furniture and’ run around biting the walls until the house was destruction from one end to the other. He knell, that I liked to dress him in nice clothes, so he used to rip the bus tons off his shirts and used to go in his pants.” When he got violent Pat punished him. But she got terribly distraught, and for Bill! the pleasure of seeing her upset made any punishment worthwhile. Sometimes he attacked her whit all the fury in his small body, and going for her throat with his teeth. Anything that wasn’t nailed down or locked up — soap powder, breakfast food — he strewed all over the floors. Then, laughing wildly, dragged Pat to come see it.

She had to face her problem alone. It was impossible for her to keep any household help. Once Billy tripped a maid at the head of the stairs, then lay on the floor doubled up with laughter as she tumbled down. And Billy was so cunning that his father didn’t know what was going on. “Pat would tell me about the things he did while I was away, but I couldn’t believe her,” he says.

As time went on, even his father realized that they had a monster on their hands. Enrolled at a school for retarded children, Billy threw the whole institution into an uproar. Obsessed with a certain record, he insisted on playing it over and over for hours. He sent the children in his class into fits of screaming misbehavior. “He was just like a stallion in a herd of horses,” his mother says. Billy ruled his teacher with his tantrum until, a nervous wreck herself, she could no longer stand to have him in the class. “He became a school dropout at the age of 5,” says Pat

At home things were taking a macabre twist. Billy had a baby brother now, and at any opportunity he tried to stuff the infant into the toy box and shut the lid on him. His parents had bought him a doll which resembled the baby, and which they called by the baby’s name, Patrick. Every morning Pat found the Patrick doll head down in the toilet bowl. Terrified of what might happen she never left the two children alone together.

As he grew older Billy’s machinations seemed far too clever for a retarded child, and so his parent took him to see another expel There, given a puzzle to test his intelligence, Billy simply threw the pieces against the wall. The experts delivered the same old verdict: Billy was retarded.

At the retarded children’s school, the youngsters occasionally got hamburgers for lunch from a drive-in chain. Inexplicably, Billy became hooked on them hooked to the point that he would starve himself rather than eat anything else. Within a few weeks Pat and her husband became slaves to Billy’s hamburger habit. Every morning and every night Billy’s father stood in line at the drive-in and bought cheap hamburgers by the sack. Eventually he became so embarrassed— he is a small, thin man, and the waitresses had begun to look at him curiously — that he cruised the city looking for drive-ins where he wasn’t known. Billy ate three cold, greasy hamburgers for breakfast, more for lunch, more for dinner. “He was like Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend.” Pat shudders. “To make sure he wouldn’t eat them all at once lid hide them all over the house — in the oven and up on shelves. In the middle of the night he’d be up prowling around, looking for them. A month later I’d find ossified hamburgers in hiding places I’d forgotten.”

When they were out driving with Billy, they had to detour around any drive-ins. Billy flew into such a frenzy at the sight of one that he frothed at the mouth and tried to jump out of the moving car.

Pat knew that the boy could not survive on a diet of cheap hamburgers. She took him to places where they served hamburgers of better quality; Billy refused to eat them. Frantic, she contrived an elaborate ruse. Buying relish and buns from the drive-in, she bought good meat and made the patties herself She put them into sacks from the drive-in, even inserting the little menu cards that came with the drive-in’s orders. When she presented this carefully recreated drive-in hamburger to Billy, he took one sniff and threw it on the floor

Then there was Billy’s Winnie-the-Pooh period. Billy had become obsessed with a particular kind of Teddy bear, marketed under the trade name of Winnie the Pooh. Without it, he’d go berserk. The family was moving about a good deal then, and Pat was terrified that she would have no replacement when Billy lost his bear or tore it up. “Just to make sure I’d never run out, I found where to buy a Winnie wherever we might be going. l knew a place in San Diego and a place in La Jolla and a place in San Francisco. I even knew where to buy a Winnie in Las Vegas. I always kept some in reserve just so we wouldn’t run short in a hotel. Our whole life became one long Winnie trip. Once, when we were moving, Winnie got put into the van by mistake, and we had to have the movers take everything out so we could find it. We were afraid to make the trip with Billy without a Winnie bear — we were starting to go nutty ourselves.”

Pat became so desperate that when she found something that frightened the boy, she used it as a weapon of self-defense. The one thing that did the trick, appropriately enough, was Alfred Hitchcock. For some reason, when Hitchcock came on television Billy took off like a rocket and hid under the bed. When Pat learned that photographs of Hitchcock had the same effect, she started cutting them out of TV magazines. When Hitchcock appeared on LIFE’S cover, she bought a whole stack of magazines and stuck the covers up all over the house — on the icebox to keep Billy from opening it, on the fireplace to keep him from crawling around in it. When she took a bath she put Hitchcock pictures outside the bathroom door so Billy would leave her in peace.

“It was crazy,” Pat remembers. She was at bay in a house with the doors bolted and the windows locked, the baby stuffed in the toy-box and the Patrick doll with its head in the toilet, hamburgers hidden on shelves and a closet full of cast-off Pooh bears and the breakfast food strewn all over the floor, and little Billy raging around like an animal, attacking pictures of Alfred Hitchcock with a long stick.

By now Billy was getting so big and strong that Pat could hardly control him physically, and she and her husband were thinking of building a fence around their house to keep him from endangering others. But before doing so, they took him to one more psychiatrist. “You can’t build a fence high enough,” the psychiatrist said flatly. “He’ll be a Frankenstein monster. Put him away.”

Miserable though they were, Pat and her husband couldn’t stand the thought of abandoning the boy to an institution. “We were supposed to put him away and throw away the home movies and tear up the scrapbook pictures,” she said. “We just couldn’t do it.”

A few weeks later a psychiatrist connected with the retarded children’s school told Pat and her husband that Billy might not be retarded but autistic. He suggested they take him to the Neuropsychiatric Institute at UCLA where Dr. Lovaas and his colleague, Dr. James Simmons, a psychiatrist, were choosing autistic children for a new experimental program. Pat and her husband were enthusiastic, even though they knew, about the punishment that Billy would be subjected to.

Their one fear was that Billy, erratic child that he was, would flunk his audition in front of Lovaas. But they knew that one of the criteria was that the children accepted must like to eat, and must be willing to expend a lot of energy to obtain food. So Pat and her husband talked things over, and they had an idea.

When they took Billy to see Dr. Lovaas, they made a stop on the way at the drive-in. Billy, given the hamburgers during the interview, passed the entrance exam with flying colors.