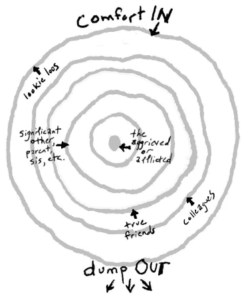

In 2013, the clinical psychologist named Susan Silk created the Ring Theory that explains the harm that is caused to people already in stressful situations by their very own support network.

The reason it’s a “ring” theory is because Susan places the person who is aggrieved or afflicted in the center (such as herself when she had breast cancer) and her support network is represented as the circles and rings surrounding her.

In the innermost ring you’ll find their significant other(s), parent(s), sibling(s), etc. The second innermost ring are where your “true” friends are. The next level is labelled colleagues and the outermost ring Susan describes as the “lookie loo’s”. In essence, this visually lays out how “close” people are to your specific stressful situation.

Based on this multi-ring structure, communication to avoid accidentally hurting someone in these vulnerable situations means that the person in the center ring can express themselves however they need to to anyone in order to successfully navigate their situation.

There are only two rules: comfort in and dump out.

Everyone’s role is to be supportive toward those closer to the center than they are but can be supported by those farther from the center than they are. This means someone like Susan’s sister (who is on the first ring around the center) could vent to a colleague about Susan’s breast cancer, but not to their parents or Susan herself. If Susan’s sister were to vent directly to Susan about it, this could cause accidental harm to Susan. Her sister’s job is to support Susan. If her sister needs support, she must seek it from elsewhere, not from Susan.

Ring Theory regarding Disability

I love the communication structure that Susan Silk created so I decided to explicitly apply it to disability. And personally, I apply it to myself when I talk to people about being autistic.

When applied to a disability, the disabled person is always in the center of the ring. When you talk to a disabled person about the disability they have, you do not complain to them what it’s like to live with someone who has the same disability in your household. In that scenario, you are somewhere on the outer ring and complaining about that disability is dumping in on the disabled person. They will likely relate more to the person you’re complaining about than you and it will ultimately affect them negatively, only affirming what they believe people think about them.

It’s important to remember that this communication model is not representative of a specific person, but rather a subject or topic.

For example, my child and I are both autistic. My partner is not. One might think it is appropriate for my partner to complain to me about our child when she is in a sensory seeking mood and being incredibly loud because you’d place our child in the center of the ring and my partner and on the innermost ring for living with her.

However, that’s not how it works. In this hypothetical scenario, my partner is dumping out about autism and sensory seeking behavior. Because I’m also autistic and occasionally engage in sensory seeking behavior, I’m also in the center ring with my child. I would process his comments and feel bad about myself because of course I’d be thinking, “Do you feel this way about me too?”

Now this doesn’t mean my partner does not need comfort or support. He does. His feelings are valid too. I’m just not the appropriate audience for him to be dumping out on for that topic.

This also comes into play when we see parents publicly announcing their dislike for their children’s disabilities, saying things like, “I don’t love autism, I love my child.” It’s just dumping out on any autistic person who happens to witness it and it’s harmful. This is especially hard to avoid in intersectional spaces where you have a disabled parent watching other parents dumping out in a group seeking for others to comfort in. In this case, be kind. Add trigger warnings so those affected can scroll on and you can receive the comfort you need and deserve too.

References

- Susan Silk and Barry Goldman, “How not to say the wrong thing” (Apr. 7, 2013). Los Angeles Times.

![An infographic titled Ring Theory: Mitigating Harm with Communication. The graphic are 5 circles of difference sizes all laid on top of each other. The center circle is white with the label disabled person. The circle around that is 25% grey and labeled those living with them. The circle around that is 50% grey and labeled closest friends & family. The circle around that is 75% grey and labeled extended friends & family, coworkers. The final circle is black and labeled [internet] strangers. To the left of the labels is a rainbow arrow pointing from outside in labeled Comfort In. To the right of the labels is a rainbow arrow pointing from the inside out labeled Dump Out.](https://just1voice.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/07/Ring-Theory-300x300.png)